“Genetic Studies Lack Diversity, and It’s a Problem”

Biobanks—large collections of genetic data linked with medical data—provide a foundation for current medical genetics research.

The problem is that biobanks, and other large datasets used for genetic studies, are composed predominantly of white individuals with European ancestry. I

t means that non-white populations are missing out on breakthroughs in medical genetics.

While working at a research hospital in Boston, I volunteered to participate in a genetic study. Actually, I volunteered to participate in a lot of genetic studies. I donated a blood sample to be included in a new “biobank” that the hospital was starting. My anonymized medical record would be linked to my blood sample and genetic data, and with thousands of other samples, could be analyzed by any number of researchers for future studies, so long as they asked permission from the hospital.

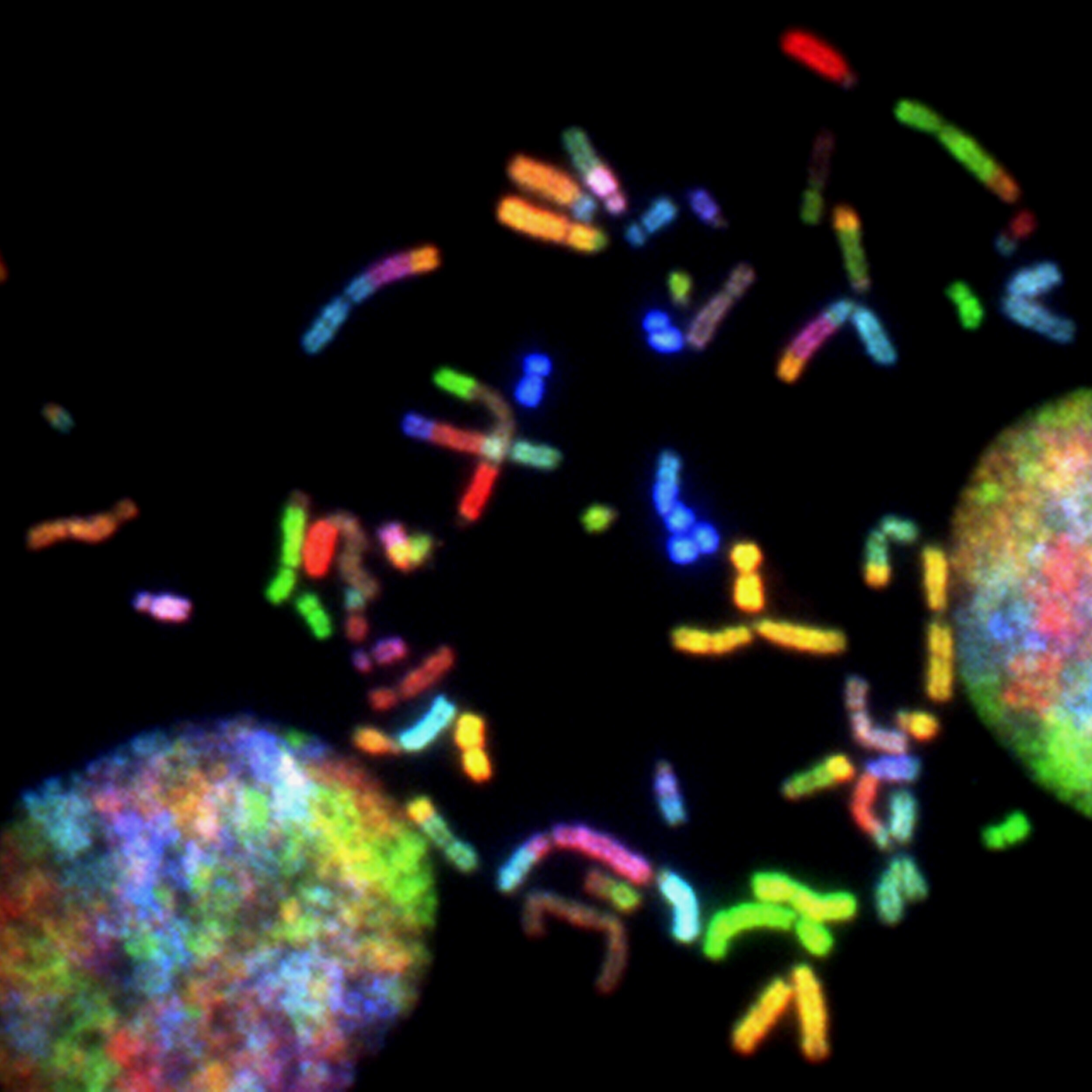

Biobanks—large collections of genetic data linked with medical data—provide a foundation for current medical genetics research. Studies that seek to identify the genetic causes of a disease essentially ask the question: If there is a group of healthy individuals and a group of individuals with the disease, can we find a set of genetic markers that distinguish these groups? Biobanks provide the collections of individuals, the genetic data, and the medical data to perform these studies.

The problem is that biobanks, and other large datasets used for genetic studies, are composed predominantly (more that 80%[*]) of white individuals with European ancestry. There is a growing representation of Asians, but Africans, African Americans, and Hispanics make up less than 10%* of the subjects in these collections. This is a problem for several reasons.

Foremost, it means that non-white populations are missing out on breakthroughs in medical genetics. Discoveries made in white populations are not always translatable to non-white populations. Predictive genetic tests like polygenic-risk scores, which use a combination of genetic markers to predict an individual’s risk for disease, often perform poorly and with unpredictable biases in Hispanics and African Americans.

Additionally, the lack of diversity in genetic studies is detrimental for everyone. Ethnic homogeneity in these studies makes it difficult to distinguish meaningful associations between genetic mutations and a disease from statistical noise. For example, a mutation could be uncommon in white Europeans and be found more often in individuals with a certain disease, leading researchers to believe there is some link between the mutation and the disease. However, this same mutation may be very common in Asians. Knowing the mutation’s frequency and lack of association with disease in Asians, researchers can correctly conclude the mutations is likely benign and not linked to the disease.

It’s good news that efforts are being made to enhance diversity in genetic studies. Several projects have already increased representation of Asians, and others are working to increase representation of Africans and Hispanics. As these projects develop, however, it’s important to ensure that the benefits derived from the greater representation and diversity in genetic studies are equally distributed to all participating groups, and do not remain sequestered to certain populations.

[*] Popejoy, A. B., Fullerton, S. M. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. (2016)